For sometime now I’ve been observing a lot of discussion around caches & their implementations on LinkedIn and my batchmates from NYU (be it for software interviews, optimizations or system design in general).

And usually these discussions mostly involve implementations in JAVA, and are mostly not thread safe. I thought I’d just jump into this action, and propose these caches in Python and better, thread-safe.

How to recall which one’s which?

LRU Cache : Least Recently Used cache : Evict the oldest used data

MRU Cache : Most Recently Used cache : Evict the latest used data

As is the best choice for data structure in this scenario, we use a doubly-linked list along with a dictionary.

Here’s what our doubly-linked list node looks like:

class Node:

def __init__(self, key = None, value = None):

self.key = key

self.value = value

self.prev = None

self.next = None

Before LRU or MRU cache, let’s just think about a cache first.

class SomeCache:

def __init__(self, capacity: int):

self.capacity = capacity

def get(self, key: int) -> int:

pass

def put(self, key: int, value: int):

pass

Irrespective of any kind of backend or logic, any cache exposes 2 APIs: get and put . The user does not have access to any other function, attribute or API logic. And only these 2 APIs are going to access any other functions and attributes in the space. Hence, we need to do something about thread-safety only here in these 2 APIs.

We’ll discuss about cache logic later, let’s talk about thread-safety now. We can use the Python multi-threading synchronization primitive: Lock() . Ideally I also looked into using RLock() which is a locking primitive for RE-Entrant Lock . But it is more suited for cases, where the same thread needs to acquire the same lock multiple times in succession. Currently this is not our case, maybe perhaps if the underlying logic and functions were also exposed for other APIs or usage, then we might have had to use it. So here is what our cache structure looks like with thread-safety:

import threading

class SomeCache:

def __init__(self, capacity: int):

self.capacity = capacity

self.lock = threading.Lock()

def get(self, key: int) -> int:

with self.lock:

# cache logic

pass

def put(self, key: int, value: int):

with self.lock:

# cache logic

pass

Notice, how we have created a

Lock()object in the__init__of class. I noticed a common mistake in cache implementations on the net, where people create a lock object inside theget & putAPIs. This does not however ensure thread-safety. It is actually creating a new lock everytime either of those APIs are called. And since the locks in both of these APIs are different this way, even when they areacquired, access to critical-section is not limited as it is desired.

LRU Cache

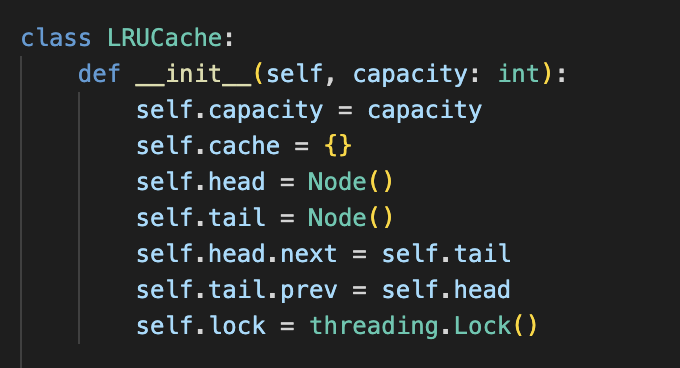

class LRUCache:

def __init__(self, capacity: int):

self.capacity = capacity

self.cache = {}

self.head = Node()

self.tail = Node()

self.head.next = self.tail

self.tail.prev = self.head

self.lock = threading.Lock()

def _add_node(self, node: Node):

node.prev = self.head

node.next = self.head.next

self.head.next.prev = node

self.head.next = node

def _remove_node(self, node: Node):

prev = node.prev

new = node.next

prev.next = new

new.prev = prev

def _move_to_head(self, node: Node):

self._remove_node(node)

self._add_node(node)

def get(self, key: int) -> int:

with self.lock:

if key in self.cache:

node = self.cache[key]

self._move_to_head(node)

return node.value

else:

return -1

def put(self, key: int, value: int):

with self.lock:

if key in self.cache:

node = self.cache[key]

node.value = value

self._move_to_head(node)

else:

new_node = Node(key, value)

self.cache[key] = new_node

self._add_node(new_node)

if len(self.cache) > self.capacity:

tail = self.tail.prev

self._remove_node(tail)

del self.cache[tail.key]

Let’s start with the __init__ . We initialize a Python dict to substitute as cache, head and tail nodes for our doubly-linked list and a locking primitive. We also set head node’s next node as the tail node and tail node’s previous node as the head node.

For _add_node , we always add a node to the front of doubly-linked list because we need to preserve an ordering in doubly-linked list -> such that latest used data item is in the front. This is a O(1) operation.

For _remove_node , here is the beauty of double linked list. We can remove any node from the list again in O(1) operation.

For _move_to_head , we simply are removing a node from the double-linked list and adding them back to the list in the front. As both subsequent operations are O(1), this essentially is also an O(1) operation.

Now for get API, we simply check if the given key exists in the cache. If it does not, we simply return -1. If it does, we lookup for that key, but before returning its value, we first move that node to head because we need to preserve an ordering in doubly-linked list -> such that latest used data item is in the front. Speaking strictly in terms of average case, the time-complexity of this API comes at O(1) operation. (This is because Python dictionaries are implemented using hash functions in backend, and average case time complexity for lookups is indeed O(1) but in worst case it escalates to O(n)).

For put API, we do similar check as in get API. If the key is already in the cache, we simply move the existing node to the head. Otherwise, we create a new node and add it to the cache and our doubly-linked list. One important check over here, when we add a new node, we must check if our cache size is being breached. If it is, then comes our LRU Cache Eviction policy in action . We remove the node at the tail of our doubly-linked list. Because at each operation, we have maintained that the used data items are moved to front of our doubly-linked list. Hence, whatever is at the last node must be the least recently used and we evict this oldest data.

MRU Cache

class MRUCache:

def __init__(self, capacity: int):

self.capacity = capacity

self.cache = {}

self.head = Node()

self.tail = Node()

self.head.next = self.tail

self.tail.prev = self.head

self.lock = threading.Lock()

def _add_node(self, node: Node):

node.prev = self.head

node.next = self.head.next

self.head.next.prev = node

self.head.next = node

def _remove_node(self, node: Node):

prev = node.prev

new = node.next

prev.next = new

new.prev = prev

def _move_to_head(self, node: Node):

self._remove_node(node)

self._add_node(node)

def get(self, key: int) -> int:

with self.lock:

if key in self.cache:

node = self.cache[key]

self._move_to_head(node)

return node.value

else:

return -1

def put(self, key: int, value: int):

with self.lock:

if key in self.cache:

node = self.cache[key]

node.value = value

self._move_to_head(node)

else:

if len(self.cache) == self.capacity:

mru_node = self.head.next

self._remove_node(mru_node)

del self.cache[mru_node.key]

new_node = Node(key, value)

self.cache[key] = new_node

self._add_node(new_node)

You’ll notice that almost the entire logic remains same. It is only in the put API that one recognizes the difference. The only change is in our eviction policy here. Notice the code change inside the if condition when we add a new node here. Whenever the capacity of our cache is breached, now we have to evict the latest used data item. And since we maintain that property in our doubly-linked list, we know that it is pointed by the head of our list. We simply obtain this node directly and remove it from our cache as well as the doubly-linked list.

How to test these caches?

cache = LRUCache(2)

cache.put(1, 1) # DLL: 1

cache.put(2, 2) # DLL: 2<->1

print(cache.get(1)) # Output: 1 | DLL: 1<->2

cache.put(3, 3) # DLL: 3<->1 (because 2 was removed due to LRU policy)

print(cache.get(2)) # Output: -1

cache.put(4, 4) # DLL: 4<->3 (because 1 was removed due to LRU policy)

print(cache.get(1)) # Output: -1

print(cache.get(3)) # Output: 3 | DLL: 3<->4

print(cache.get(4)) # Output: 4 | DLL: 4<->3

cache = MRUCache(2)

cache.put(1, 1) # DLL: 1

cache.put(2, 2) # DLL: 2<->1

print(cache.get(1)) # Output: 1 | DLL: 1<->2

cache.put(3, 3) # DLL: 3<->2 (because 1 was removed due to MRU policy)

print(cache.get(2)) # Output: 2 | DLL: 2<->3

cache.put(4, 4) # DLL: 4<->3 (because 2 was removed due to MRU policy)

print(cache.get(1)) # Output: -1

print(cache.get(3)) # Output: 3 | DLL: 3<->4

print(cache.get(4)) # Output: 4 | DLL: 4<->3

How to confirm thread-safety?

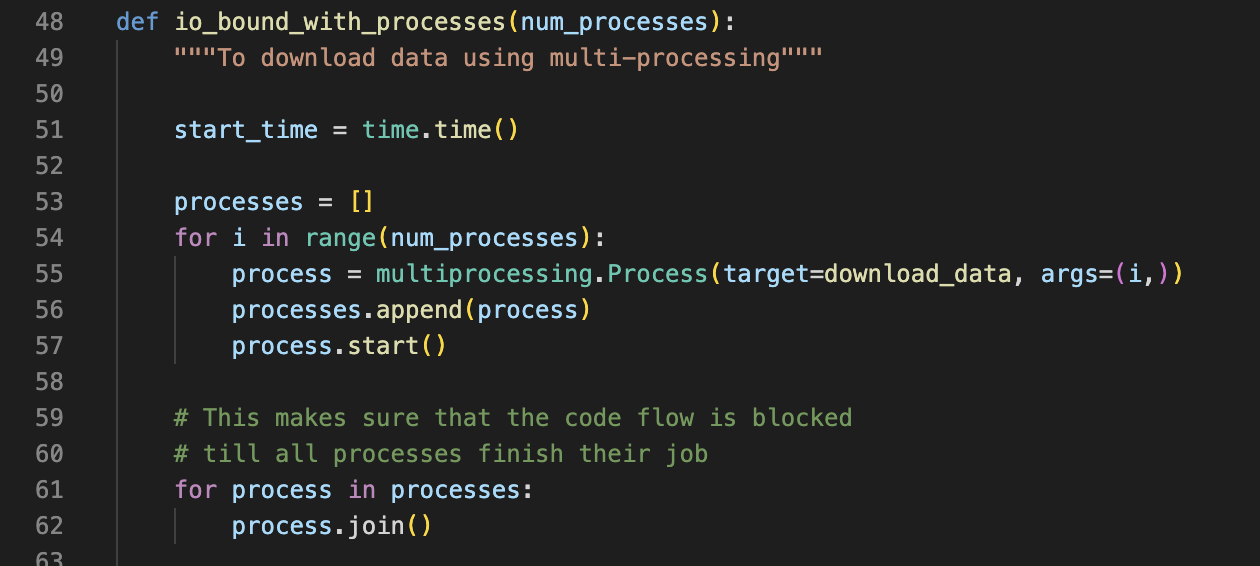

Here is basic driver code to test out the caches:

import threading

import time

from lru_cache import LRUCache

from mru_cache import MRUCache

CACHE_CAPACITY = 4

NUMBER_OF_THREADS = 5

def worker(cache, key, value):

time.sleep(1)

for _ in range(10000):

cache.put(key, value)

cache.get(key)

current_thread_id = threading.current_thread().ident

print(f"current_thread_id: {current_thread_id}")

cache = LRUCache(CACHE_CAPACITY)

# cache = MRUCache(CACHE_CAPACITY)

thread_list = []

# Create multiple threads accessing the cache concurrently

for i in range(NUMBER_OF_THREADS):

new_thread = threading.Thread(target=worker, args=(cache, i, i))

print(f"new thread: {new_thread}")

thread_list.append(new_thread)

# Start all threads

for t in thread_list: t.start()

# Wait for all threads to finish

for t in thread_list: t.join()

print(f"thread_list: {thread_list}")

# After all threads finish, check the cache contents

for i in range(NUMBER_OF_THREADS):

print(f"key: {i} | cache.get(key): {cache.get(i)}")

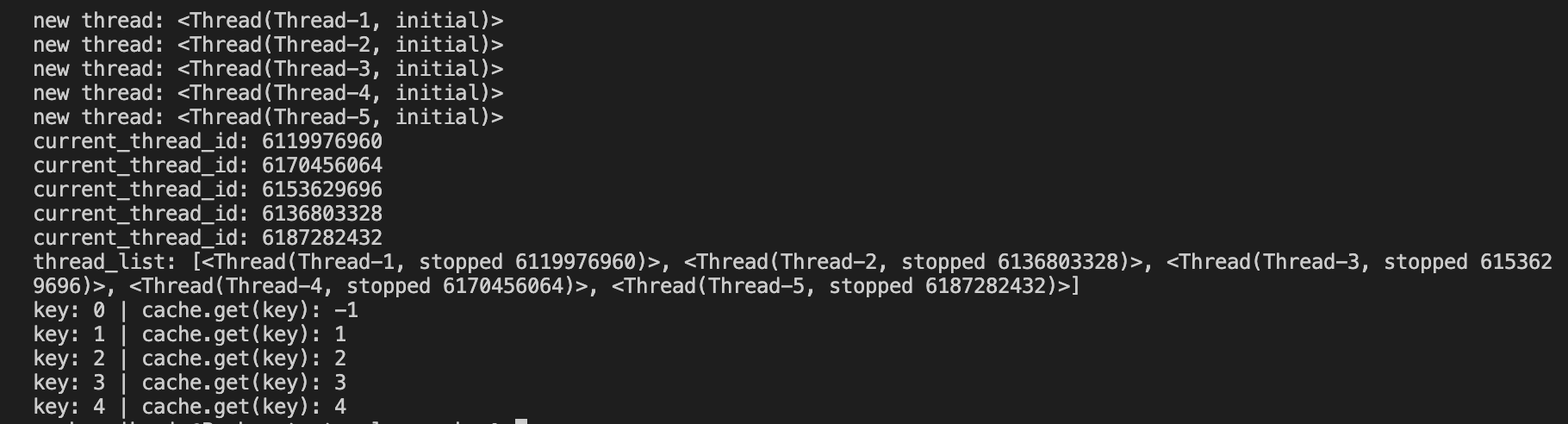

Output for the above tester code for thread-safety

Output for the above tester code for thread-safety

Thank you for reading the article! I hope you found the answers you were looking for. You can also check out this implementation of cache used in DJango backend framework of Python.

कथं विद्यामहं योगिंस्त्वां सदा परिचिन्तयन् ।

केषु केषु च भावेषु चिन्त्योऽसि भगवन्मया ॥

– Bhagavad Gita 10.17 ॥

(Read about this Shloka from the Bhagavad Gita here at sanskritslokas.com)

Find those tweets! - an NLP + Clustering cute short story

Find those tweets! - an NLP + Clustering cute short story